Over the last 30 months or so, I’ve been going on and on about the mainstay of CRAVE Guitars ‘work’, which is to share with you not only stuff about music and stuff about guitars generally but also specifically stuff about Cool & Rare American Vintage Electric Guitars. If you’ve taken a look at the web site, you’ll know that the focus tends to be on mainstream U.S. brands and, within that, if possible, some cool variations of well-established guitar models. However, perhaps stating the bleeding obvious, the guitar world is much bigger than that.

This month I’m dipping a toe in the water of some of the other guitar treasures out there. When one looks across the whole guitar landscape, antique, vintage, old, used, new, American, European, Eastern bloc, Asian, mass manufacture, boutique makers, unique luthiers, home‑made, traditional, basic, hi-tech, innovative and whacky, there is infinite variety and a veritable cornucopia of interesting and wonderful instruments to appreciate. The same goes for amps and effects of course (as colleagues into those things keep reminding me) but there’s not enough room in a single article for those as well. Besides, although I don’t claim to be an expert on guitars, I’m even less well‑acquainted the minutiae of amps and effects – that’s another ballgame altogether. The focus of this article is essentially on electric instruments.

When researching this article, it became ridiculously clear that I simply can’t do justice to every aspect of this enormous topic. I can only mention a figurative iceberg’s tip of what’s out there and I apologise in advance for the probable monumental omissions herein. Before we get going, none of the guitars covered in this article are part of the CRAVE Guitars’ family. In order to illustrate the diversity, I’ve resorted to using pictures sourced from Google Images – I acknowledge all guitar owners and photographers.

Let’s face it, love them or loathe them, the centre of the guitar universe remains occupied by the American ‘Big Two’, Fender and Gibson, along with their subsidiary companies including, respectively, Epiphone and Squier that concentrate on the budget end of the market. Incidentally, Fender and Gibson also own a number of other iconic brands that come under their wing. For instance, did you know that Fender own Gretsch, Jackson, Charvel, DeArmond and Tacoma, and Gibson own Baldwin, Kramer, Steinberger, Tobias and Wurlitzer? Until the mid-2010s, Fender also owned Guild and Ovation guitar brands.

It would be easy to fall into the trap of thinking that Fender and Gibson are massive multinational industrial giants, but in actuality, they are pretty modest business concerns compared to the sheer scale and scope of some truly global companies. Fender and Gibson are, above all, very successful brands with a strong identity, whose reach extends well beyond the music industry. This general public awareness helps to shield them from some of the economic, social and technological pressures facing them. Business fortunes, however, go in cycles and the ‘Big Two’ have had their ups and downs. Both companies, along with many others, were taken over in the 1960s, leading to a period of corporate complacency and weakness that opportunistic competitors were able to exploit. While they have been able to rejuvenate their image, they are now dealing with a radically different global context.

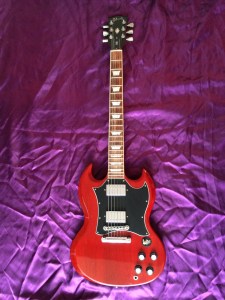

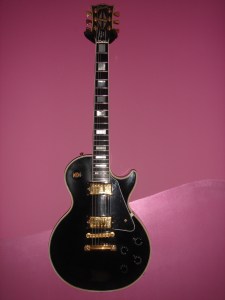

While the ‘Big Two’ are fortunate to have genuinely iconic products including Fender’s Stratocaster, Telecaster and Precision bass, and Gibson’s Les Paul, SG and ES-335 (among others), this otherwise enviable position can also constrain them operationally. It has proved very difficult for them to innovate and stretch too far from the proverbial straightjacket imposed by their core instruments. Existing models are scrutinised minutely and often face intense criticism if they move away from the accepted recipe. At the same time, it is difficult for them to introduce all-new models, as they are often compared unfavourably with the classic mould. Without sustainable growth in a finite market, these companies are commercially vulnerable and their potential success is increasingly limited by their past. This strategic conundrum for Fender and Gibson actually creates fertile ground for other smaller firms to grasp opportunity to enter the market through differentiation, diversification and innovation, as well as imitation.

Circling around the ‘star’ of the Big Two, there are the other recognisable brands such as Rickenbacker, Danelectro, Guild, Ovation, Music Man (now part of the Ernie Ball corporation), G&L, and, as well as the aforementioned Gretsch (the Gretsch family retains major influence as part of Fender) and relative newcomers such as PRS. There are other companies that don’t immediately spring to mind but which have enormous presence in the industry. I include Peavey here, as one of the world’s largest musical manufacturing company. Then there are the other recognisable ‘independent’ American manufacturers that tend to focus on niche markets, such as BC Rich, Dean, Jackson, Alembic, Carvin, Schecter, Steinberger, Suhr, Parker, Heritage, etc. At the same time, some major US guitar companies focus predominantly on acoustic guitars, such as Martin and Taylor.

There is an incredible history surrounding brands that have either disappeared completely or those that have gone, some of which have now been resurrected, e.g. Supro, Airline, National, Dobro (acoustic, now part of Epiphone), Bigsby, D’Angelico, D’Aquisto, Silvertone, Kalamazoo, etc. American guitar manufacturers suffered particularly badly in the 1960s and 1970s as a result of multiple pressures including falling production quality, increasing manufacturing costs (including union labour), and hostile competition from high quality cheap imports from the Far East.

As you might expect, the history of many of the brands already mentioned goes back to the early-mid 1900s (or even further), which means that there are plenty of very cool vintage guitars floating around. In the guitar world, age doesn’t mean valuable – it is the combination of age, rarity, quality originality and current condition that matter for those with an eye on the dollar value. While the Big Two tend to command the premium prices, pretty much across the board, there are plenty of bargains to be had by looking more broadly at these, sometimes ephemeral makes. I recently come across an early 1960s U.S. Airline in all‑original clean condition that went for a little over £300GBP. These never were top‑of‑the‑range instruments back in the day, and they can be picked up as bargain vintage instruments now. Some of these leftfield guitars present low-risk options for entry into the vintage market if you research carefully and don’t expect too much. History suggests that, in all likelihood, they won’t accumulate vintage value very quickly without major artist association. Look around and there are gems to be found from under-the-radar guitar makers. Some are very nice, including Washburn, Hondo (mainly copies), Mosrite, Harmony, Kay, Valco (maker of a number of other brands), etc.

Moving away from the American continent, Europe also has a long tradition of great musical instrument manufacture, with brands such as Vox, Höfner, Baldwin, Burns, Watkins, Framus, Hagstrom, Hohner, Shergold, Hoyer, Wandre, Bartolini, Levin, Goya, Welson, along with newer entrants such as Warwick, Duesenberg and Vigier, Some of these were prolific during the ‘golden years’, capitalising on the rapidly moving musical paradigms of the 1960s and 1970s. A post-war embargo on American guitar imports certainly helped European brands (and bands) get a foothold and to prosper up to the early-mid 1960s. While, as in other markets, the quality of European guitars varied considerably, many models have become synonymous with the period and, as a result, highly collectable, for instance, the teardrop Vox guitar used by Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones or the Höfner violin bass used by Paul McCartney of The Beatles.

Even further away from America, the Japanese companies competed head on with the American brands in the 1970s. Plenty of the budget guitars were blatant copies of American guitars, which resulted in protracted litigation to protect U.S. patents and trademarks. Many ‘older’ guitarists may remember copies from the likes of CSL and Columbus, as well as Ibanez. Japanese firms didn’t just replicate American designs; some also produced original designs and have retained a credible reputation over time for quality and consistency, including their dominant brands – Yamaha and Ibanez. Takamine, which focuses predominantly on acoustic guitars, is also Japanese. There have been plenty of Japanese names that are or have been familiar, including ESP (and subsidiary LTD), Roland, Italia, Aria, Tokai, Teisco, Greco, Guyatone, Apollo, Kawai, Kent, Westone, etc. Many of the instruments made by Japanese companies in the 1960s and 1970s (including some copies) are now becoming very collectable in the off‑the‑beaten‑track vintage niches. If you want some truly whacky vintage designs at reasonable prices, take a look at Japanese guitars. Plenty of people now specialise in conserving these vintage Japanese/Asian instruments.

The old Eastern Bloc countries have also produced a wide range of brands catering for home-grown musicians. The strategy of government-owned manufacture was partly nationalistic, in that they were required to protect their home market from capitalist imports from both the west and east. Many of these guitars were typically utilitarian with little in the way of flamboyance. Many of these brands will be little known in the western world, even now. As you might expect, there are experts who concentrate on collecting these communist bloc guitars for posterity. The ones that have penetrated the western markets offer something different from, and cheaper than, the mainstream names. Look out for names like Aelita, Elgava, Formanta, Migma, Musima, Odessa, Stella, Tonika, Marma (East Germany), Jolana (Czechoslovakia), etc.

There are a few other territories that have developed their own guitar manufacturing, including Godin and Eastwood in Canada and Maton in Australia. In addition, there are a large number of unmarked guitars out there with no means of identifying age or source. Some can be traced back to similar designs by known manufacturers while the creators of others are lost in the mists of time and geography. These ‘pawn shop’ guitars are often poorly made and may be considered curios, although, there are aficionados looking to conserve the more vernacular heritage.

The modern-world picture is far more complicated and can’t be talked about in terms of familiar regional territories. Some multi-national companies, including Fender and Both Fender and Gibson have their headquarters in the US and produce large numbers of their subsidiary ranges in other countries. Some brands are designed in the US and constructed offshore. Some are assembled and quality checked in the US from parts made elsewhere. Larger companies have international distribution operations that channel product to dealership networks within economic regions, e.g. Fender UK servicing the European Union (at the moment!). Others have to manage distribution through networks of independent dealers. Some smaller companies have to rely either on local markets or alternative methods of distribution, direct or indirect. Some companies make instruments that are branded by one or more retail chains. A classic example is Silvertone whose instruments were made by Danelectro, Kay and others, sold through Sears & Roebuck department stores and mail order (remember that?). Similarly, many of the diverse Japanese brand names were actually made by a relatively small number of manufacturers, e.g. Kawai and Teisco.

Another feature of new millennium guitar building is the explosion in bespoke guitar building, either by small specialist companies or individual luthiers. Low volumes, creative designs, alternative materials, custom features, and high quality tend to characterise the sub-industry but there are always exceptions to the rule. There have, pretty obviously, always been bespoke builders catering for the well‑heeled or professional musicians’ need and this has led to further opportunities that are difficult for the mass manufacturers to match. In response, the larger manufacturers, including Fender and Gibson, created custom shop operations to provide tailored services for individual clients. Custom shops also heralded the explosion in vintage-styled recreations and the more recent craze for relic finishes, both building on the growth of interest in vintage guitars.

Remember, even the (now) big companies had to start somewhere, usually with an inspirational leader, visionary pioneer or commercial entrepreneur at the helm, often working on their own or in a small workshop. Many of today’s big brands started out with some names you might just recognise, including Friedrich Gretsch and son, Fred Gretsch Jr, Orville H. Gibson, Christian Frederick Martin, Adolph Rickenbacker, Nathan Daniel (Danelectro), Epaminondas Stathopoulo (Epiphone), and one Clarence Leonidas ‘Leo’ Fender. More recently, Paul Reed Smith has earned a place amongst this exlusive group. Even these industry giants relied on other key individuals and their skills including John Dopyera, George Beauchamp, Lloyd Loar, F.C. Hall, Les Paul, Ted McCarty, George Fullerton, Ray Dietrich, Roger Rossmeisl, etc.

Other well-known names span out of larger companies, for instance, Travis Bean, well known for metal-neck guitars, split from Kramer. Kiesel Custom Guitars is another example, producing some astounding instruments having been formed following the splitting up of American company Carvin in 2015. Perhaps the most successful modern entrepreneur is Paul Reed Smith of PRS Guitars, based in Maryland USA since 1985. While growing his reputation, Smith wisely sought advice from Gibson’s ex‑president Ted McCarty to mentor him, and several PRS models now proudly bear McCarty’s name. The tradition continues with renowned luthier Joe Knaggs setting up his own prestigious guitar company after leaving PRS, producing some wonderful instruments in relatively small numbers.

One of the most celebrated and influential craftsmen to exploit niche demand in the 1960s was Lithuanian immigrant to the UK, Tony Zemaitis who made some very remarkable guitars for some very remarkable guitarists. Zemaitis’ legacy can clearly be seen in other current models from the likes of Duesenberg and Teye, as well as the Japanese company that currently carries on Zematis’ illustrious name.

There have been many excursions into the application of alternative materials to wood. The use of metal in guitar production was pioneered by the likes of National and Dobro in their resonator guitars as a means of producing more volume from acoustic guitars in the pre‑electric era of the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1960s, Valco used fibreglass (coined Res‑o‑Glas) for futuristic designs in the 1960s, such as the stunning National Newport. More recently, acoustic maker, Ovation, used a variation of fibreglass (lyrachord) on its bowlback instruments. Zemaitis experimented with other materials in his guitar construction and many others have followed suit, including the aforementioned Kramer/Travis Bean. Around the same time, there was a ‘fad’ for acrylic guitar bodies, perhaps the most well-known proponent being Dan Armstrong who used acrylic for parent company Ampeg.

On this side of the Atlantic, another luthier has set the bar for innovative use of metal; French luthier, James Trussart, Italian company XoX Audio are making some nice instruments out of carbon fibre. 3D printing also presents opportunities for greater use of plastics and metals in guitar production. Some luthiers have experimented with stone as part of the construction but it is not common – or very practical. With ever increasingly stringent restrictions on sourcing, use, sale and movement of hardwoods commonly used in guitar production, expect wider use of alternative sustainable materials in the future.

There are hundreds if not thousands or even tens of thousands of guitar makers out there, all wanting a proportion of the overall demand for great guitars. Here are a very few notable names from all around the world to keep an eye on, including (in no particular order); Collings, Stone Wolf, Flaxwood, Palm Bay, Hutchinson, Emerald, Ed Roman, Suhr, Mayones, Nik Huber, Matt Artinger, Tom Anderson, Patrick James Eggle, Fano, Gus, Goulding, Prisma, Frank Hartung, Michael Spalt, Michihiro Matsuda, TK Smith, Rick Toone, Carillion, McSwain, John Backlund, Reverend, Ron Thorn, John Ambler, Mule, Tony Cochran, Walla Walla, Ezequiel Galasso, Langcaster… The list could be endless as there are just too many great guitar buillders out there to mention and apologies to those I’ve left out and, sorry, I can’t post pictures of every one – I wish I could. The point, I guess, is to broaden one’s perspective and perhaps open one’s mind to a wide range of other possibilities beyond the obvious in-your-face guitar shop fare. I don’t usually proffer advice but on this occasion, I would simply just say, take a look out there and you might just find something weird and wonderful that you probably didn’t know existed. I regularly feature some of this wonderland of goodies on Twitter for those that may want to take a look (@CRAVE_guitars).

For the amateur hobbyist or artisans with aspirations of becoming the next notable designer, there are now plenty of DIY kits for everything from generic product to some quite fancy customised guitar construction. Access to information the Internet provides plenty of plans and specifications for people to design and build almost any type of instrument without the need to track down books or luthiers willing to share their knowledge. Experimenting in this way can present all sorts of opportunities to be taken. What about you?

Renovation ‘husk’ projects are probably best avoided unless you really know what you’re doing, as there’s probably a reason why they are in that state to begin with. For some, though. a ‘bitsa’ guitar may make an ideal low cost player’s guitar. My lack of practical skills prevents me from trying out a DIY (re-)build beyond my limited capabilities. Besides, given CRAVE Guitars’ fundamental raison d’être, I simply can’t create an authentic American vintage guitar.

I hope that this article has given a tiny indication of the beauty and multiplicity of guitars out there. That’s without going into oddities with unconventional string configurations, double (or more) necks, hybrid instruments, etc. It is this fascination with making things different while also keeping things the same that is quite inspirational and, I think, pretty unique to guitars, at least on this sort of scale. We are blessedly spoilt for choice and there are some ridiculously good guitars out there for very reasonable prices without experiencing the diminishing returns associated with esoteric exotica. Ultimately, this clearly indicates that there is something for everyone with an interest in the world’s favourite musical instrument.

So… you may ask… what’s my favourite out of everything covered here? Truthfully, I can’t say; I find guitars endlessly beguiling and preferences vary continuously. It would be unfair to single any one brand or model from the others. As my obsessive quest for ‘Cool & Rare American Vintage Electric Guitars’ continues, the CRAVE name gives a hint of bias but that is not so dogmatic that I can’t appreciate all aspects of the luthier’s art and craftsmanship. MY position is firmly ‘on the fence’. If any of the names mentioned wish to persuade me off the fence with a prime example of their product(s), I am more than happy to accommodate them (f.o.c. of course!). I optimistically await a swathe of e-mails to that effect (hint, hint).

Me? I’m off to plink a new CRAVE Guitars’ plank. The new addition to the family is something both very recognisable and very unusual at the same time. All being well, I’ll try to cover it in next month’s article. All I’ll say at this juncture is that it is definitely one that fits the Cool & Rare American Vintage Electric Guitar bill very aptly while also strongly dividing opinion. Intrigued? The lengths we go to, to bring you guitar ‘stuff’. Watch this space…

CRAVE Guitars ‘Quote of the Month’: “There is a finite limit to the amount you can know, there is no limit to the amount you can imagine.”

© 2017 CRAVE Guitars – Love Vintage Guitars.